Part 2 - Mix Prep

Bob was now ready to send me the tracks. We did this via Dropbox. which actually didn’t go as smoothly as I’d hoped (mainly due to my suggestions, given in the hope that I could keep some room in my rapidly ballooning Dropbox), but we got there in the end.

Initially the session included a total of 21 tracks - As a mixer, I love seeing a concise and economic use of tracks - it’s generally always a good sign. Tracks were as follows

9 Mono drum tracks:

kick, snare top, overhead left, overhead right, hihat, rack tom, floor tom 1, floor tom 2 & a mono room mic

1 x Bass DI (I didn’t see the reamped track Bob mentioned above)

5 x Guitar Tracks - 2 main rhythm tracks, 2 “colour” rhythm tracks & 1 Lead Solo (I didn’t end up using the DI track - these were all mic’d amps)

5 x Vocal tracks (1 lead vocal, 1 double track for choruses & other parts & 3 harmony vocals making the 3 parts of the chorus vocals)

& finally 1 “Bourbon Bell” percussion track (a bourbon bottle hit with a stick in the fashion of a cowbell)

Of course, Bob went craaaazy and added a staggering total of 3 more tracks by the end of the mix, but that wasn’t my fault at all, na ah!  More about that later, though.

More about that later, though.

Mix prep is a tedious, but vital step in every mix. It’s where I try to get all the non-creative stuff out of the way, so that eventually, I can just come in, open the session and start mixing. It usually takes me about 2-4 hours in an evening after work to do.

First, I import all the tracks into a new, clean session in Reaper. I listen down to a “faders up” version of all the tracks together, maybe soloing different tracks briefly as it plays to check everything is there that was in the rough mix.

Next, I colour code and label the tracks in my own personal nomenclature.

Usually at this point I put in markers indicating different sections of the song, so that I can move around quickly from part to part. This works fine if you have a constant tempo, as all the changes usually occur on downbeats of a bar. However after inputting the tempo Bob had given me into my DAW, it became clear that there was some movement in the tempo over the duration of the song. I tried a few close alternatives - slightly faster, slightly slower, but nothing was really nailing it down. I then decided to create a tempo map, based on the drum track.

Luckily, this is a piece of cake to accomplish in Reaper. It involves just using the “tab to transient” function to split the drum track up into bars. It’s then simply a matter of selecting the time signature, the number of bars being analysed, the specific bar length in the timeline, then getting Reaper to run the “Measure from Time Selection (Detect Tempo)” routine. It probably sounds more involved than it is, but the whole song can be done very quickly. In fact, if I was doing that specific series of actions all the time, I would probably program a “custom action” (something like the equivalent of a “macro” in word processing) to speed up the process even more.

Why go to all that trouble? you may wonder… In addition to having markers easily laid at the beginnings of bars, there are other benefits: Editing parts and moving them around is easier and faster to do at just a glance. Probably most vital to me is that, since I tend to use a LOT tempo-synched delays during mixing, I don’t have to think technically about their exact timing while I’m in the creative mindset. As I said before, the mix prep stage is where I get to deal with all this technical stuff, so I can (hopefully) just think musically during mixing.

With the tempo map in place, I could now insert the place markers in my timeline: Intro, Verse 1, prechorus, Chorus etc. Again, ease of zooming around the session in mix mode is the goal here.

What next? Gain staging & my “faux analogue” workflow. I’ve written about this before, but for rock-style mixes, I use Slate’s Virtual Tape Machine & Virtual Console Collection to emulate a traditional analogue signal chain in my DAW. This means putting an instance of each on each track in the session before the signal hits any other plugin. Why? I like the sound, and I find it actually gets me to where I want to be faster come mix time.

A beneficial byproduct of doing this is that it allows me to gain-stage the tracks I am given, so that, with my faders around 0dB, I’m not pushing so much level into the master fader that it’s clipping. Since the Virtual Tape Machine is the first in line, and it’s VU meters are calibrated to hit 0 at -18db RMS FS, it’s easy to go through the individual tracks and turn the level going into the plugin up or down to get it to sit in the “sweet spot”. This is very important for me, because I use a lot of emulated analogue plugins, which start to sound nasty if you hit them with too much level.

Next, I move on to the “money track” - the Lead Vocal. With Bob’s vocals, here is where I get to skip a usually very time-consuming step - tuning the vocals. He doesn’t need it - Killer pitch for a self-proclaimed, self-deprecating “shouter”. To quote Bob: “I just scream in tune”, with the emphasis on the IN TUNE! … So no Melodyne needed here…Next!

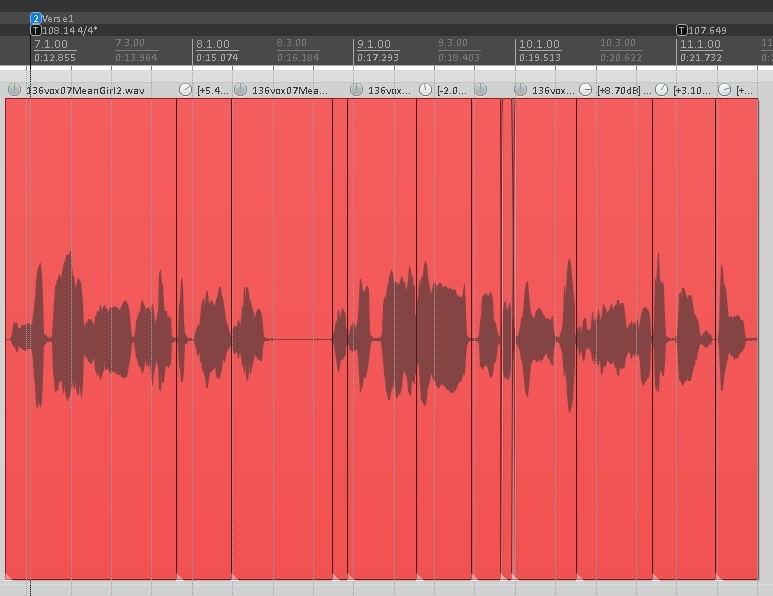

Bob’s mic technique is excellent - the dude knows how to work a microphone. That said, his style of singing is, by nature very dynamic. Without the benefit of outboard compression being “baked into” the recording on the way in, I usually find it very helpful to even out the vocal track in it’s raw state before I start processing it with anything. Reaper has a function where you can chop a waveform up into smaller clips (which automatically crossfade at the cut points). There is a little “volume knob” on the LH corner of each clip. It’s simply a matter of going through, looking at the waveforms by eye, chopping up any sections that are lower/higher than the overall average, and then turning up or down the volume knob on the clips in question until all the parts are roughly even. If you can’t picture what I’m talking about, here is a picture of one of the lead vocal sections:

Of course, it’s important to check all these edits by ear and ensure massive gain changes don’t occur in the middle of words etc. Another way of doing this type of thing is with what is called “Clip Gain” in some DAWs.

Ultimately, I find evening out the gain prior to processing makes for much smoother compression and better end results.

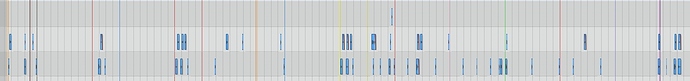

Following this, I went to work on the drums. Again, I left the drum timing unedited, as the natural human feel really suited the material. As a personal preference, with up-front rock drum sounds, I like to really tightly gate the close-miked sounds. This is easy to do manually on toms. Since they are played only every so often in the song, I edit the waveforms and remove the “dead space” between the tom hits. Rarely have I found musically useful spill in open tom mics. With “tab to transient”, this is easy and quick to do in Reaper. In the end, the tom tracks looked like this:

I also used the “clip gain” method I described for the vocals on the toms, turning up the quieter hits, and turning down the really loud ones.

The kick and snare are a different story though. The snare in particular, can be very difficult to gate accurately, and automating it to not have mis-triggers can be very tedious. A few years ago however, I came across a method that I have adopted to my way of working. I duplicate the snare track, then instantiate Slate’s “Trigger 2” plugin to trigger a very bland, highly transient sound - usually a one-shot, full velocity side stick - from each hit. This sound is never heard, as it is sent to the side chain input of the gate that I put on the original snare track. Now the gate receives a consistent “open” signal of consistent duration and volume. Now, if some hits aren’t being detected by the “trigger” snare track, I can simply chop them and “gain” them up. If a loud crash or tom has bled into the snare mic, by simply manually cutting it out of the “trigger” snare tracks’ wave form, the gate on the snare being keyed by the “trigger” track will remain closed… Perfectly clean gating, even on the lightest of grace notes.

The big advantage of this is when it comes to processing the snare - as you’d see, I get pretty radical with eq and compression of various types. Clean gating enables you to do this without fear or compromise. I used the same method with the kick, although it was less fiddly than the snare.

A side benefit of using “trigger tracks” is that I now have a ready-made sample-layering facility, should I need it further down the mix. I simply duplicate the “trigger” tracks, delete the ‘side-stick’ sample and insert whatever flavour of drum that I desire to enhance the recorded drum tracks.

The article that originally gave me the idea to use this method was this one:

http://www.soundonsound.com/people/inside-track-tom-lord-alge

We’re almost ready to go mixing. Just a case of going through and finalising the routing of the project. I don’t use folders in Reaper. I just create group tracks - A group for snare, kick, toms and overheads, all routed to a “drum buss”, which is in turn routed into a “drum master”, in case I want on of the drum elements to bypass my drum buss processing for some reason later on down the track. The “drum master” also enables “macro” automation of the drumkit as a whole. There is also a group track for rhythm guitars, one for bass (I triplicate the bass track - more on that later), and one for harmony vocals.

All these feed into a track I call a “Premaster” which in turn feeds into the final master output of my DAW. Why? The premaster enables me to drag reference tracks into the project and not have their signal being affected by the processing I have on the “premaster buss” which will eventually include compression, eq and limiting. I can put my frequency analyser, my RMS meter and my LUFS meter on the master buss, separate from my “premaster” processing to allow 1:1 analysis with my reference tracks.

Next: Onto the mix!

More about that later, though.

More about that later, though.

Its what’s commonly known as a mistake. Made by humans like me more often than than I’d prefer… I shall fix it now.

Its what’s commonly known as a mistake. Made by humans like me more often than than I’d prefer… I shall fix it now.