Thank you… thankyouverymuch! I’m here all week.

Emma we can talk about theory stuff if you want, a lot of it is not too complicated or else you can go to this website which explains theory very well.

Thanks Ingo… I just have a trouble with technical stuff… my brain sort of haemorrhages and goes into ‘flight mode’ when things become seemingly complex…

I just looked up that site and thought aha that looks interesting and then:

A chord is any combination of three or more pitch classes that sound simultaneously.

A three-note chord whose pitch classes can be arranged as thirds is called a triad .To quickly determine whether a three-note chord is a triad, arrange the three notes on the “circle of thirds” below. The pitch classes of a triad will always sit next to each other.

I mean… yes, that is a chord in the written music but why does it have to be in a key signature with FOUR flats? Perhaps you could just tell me what an E13 chord might be?

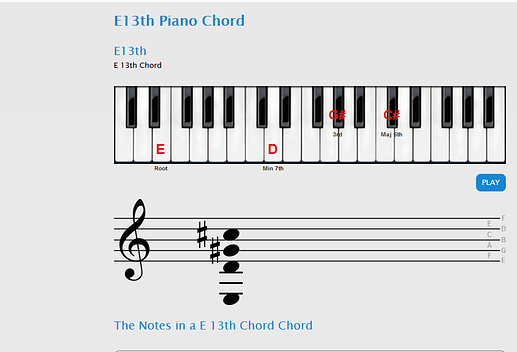

Well the short answer is that an E13 chord has in it a note which is an interval of a 13th above the E note. So for an E chord the 13th note would be C#. 13th chords have other notes as well, here’s a picture of one (it could be done other ways too.)

So to name chords you could do what I did and go to pianochord.com. To understand how chords are built and used you have to dig deeper.

Thank you! I LIKE that link, very helpful ta.

So any two notes played on the piano at the same time form an “interval” and all of the intervals have names and can be combined into chords.

The intervals are named according to their position in the scale. So in a C major scale the interval of C to D is called a major 2nd. C to E is a major third since E is the third note in a C major scale.

The common basic chords that we all use are formed by stacking intervals of a third vertically above a root note and playing them simultaneously. So a C major chord is C - E - G. C to E is a major third and E to G is a minor third stacked above it. (oops, have to talk more about that minor third thing). Continue stacking thirds and you get . . . a thirteenth chord. After that things start to repeat.

I know the basics, and I understand intervals, but for some reason I’m more attracted to the mystery of it than the theory.

On a guitar you can find all kinds of inversions that sound impressive that are pretty basic, but they would be quite a spread on a keyboard. Using open strings an octave above or below the main triad can cause dissonance or harmonics that can be a lot of fun.

I should do chord charts, because when I go back and listen to stuff I recorded a year ago I can’t figure out how to play it, which is embarrassing.

Man, this is me to a tee. I’ll get something worked up and grab the phone to record it just so I don’t lose the thread. Then I come back to it weeks or months later and it takes me a good while to figure it out again…!

To me theory is just another tool, some times it helps, often not. Things that are right in theory don’t always sound good and vice versa.

Chord charts might help us remember things but they don’t usually give inversions very well. Tab or notation would give inversions but are awkward to use. Maybe video?

WISDOM.

I had a postdoctoral fellowship at Macquarie University in Sydney in the mid-90s, and while there met a fellow US expat who was a linguist. One of his favorite sayings was, “That’s all very well in practice. But what about in theory??”

When I attempted to study Harmony at university it was a wipe out… I love the sound of consecutive 5ths and 8ves sometimes and then my work was marked wrong wrong WRONG… I found myself creatively throttled. I did learn classical piano for many years and theory was a part of that so I do know some stuff… I just found the rules for composition totally stifling. But I am aware that my current creative free flow is a result of many years of study, both voice and piano and then throwing away the rule book.

People have described me as using ‘blue notes’ and I haven’t a clue what they mean… is that like adding a note that is flattened contrary to the key? Hmmm ponder ponder…

Maybe I’ll come back and talk about parallel 5th’s and octaves later.

Blue notes are actually a little complicated. A blue note would be something typical of a blues style song; theoretically speaking the most common blue notes are intervals of a flatted 3rd, flatted 5th, and flatted 7th of a major scale but there are others too.

Normally (whatever that is) we match our scales (melodies) to our chords, so if we play a C major chord we play a C major scale to match it. Blues players will play a note not found in the C major scale, an Eb for instance, and bend it up to an E to produce a blues sound. Of course there’s a whole lot more to it, but that’s the basic idea.

If you study classical music theory the traditional approach is to begin writing chorales in a baroque style. These are simple hymns written for four voices, soprano, alto, tenor and bass. Students are required to follow an extensive list of rules for every note they write. If you follow these rules your music will sound baroque. Since our ears are conditioned by many things besides baroque music these rules don’t make a lot of sense to us.

One of these rules says you cannot write consecutive notes for any two voices that are separated by an interval of either a fifth or an octave. This is a hard rule to follow because those intervals are hard to spot in a score and don’t sound wrong to modern ears. There are various reasons given for the source of this rule but these notes sound fine to our ears today unless we are baroque musicians who will tell you that they don’t like that sound.

Today many schools offer theory classes oriented more towards contemporary music styles and students get to follow different sets of rules.

I took a basic music course in college for fun. We were working on notation, so we were supposed to write a 4 bar melody out on paper. I did the guitar part for the beginning of The Immigrant Song. The teacher said I was unimaginative.

Pretty cool and efficient way of doing it. I learned the basics of reading music playing trumpet for a couple of years.

Trying to read chords on the fly on guitar or piano just seems impossible to me. First you have to recognize it, then get your fingers there. I could probably do okay with a chart like yours, but for me it has always been memory and repetition.

haha yes… funny… I can still see in my memory the horizontal lines drawn on my manuscript in red pen screaming out the error of my consecutive 8ves and 5ths! I was simply ahead of my time, snortle.

It also explains why all the high achievers in that class wrote such similar ultra dull pieces!

Ahh! So that explains your formidable pipes! Apparently Ronnie James Dio credits his superhuman vocal and lung capacity to trumpet playing as a youngster.

None. I only know a small handful of chords so it’s not too hard to lose track of them.

As you can imagine, Emma, my collaborating with Ingo is a case of me the total nontechnical untrained musician mixing with the highly technical adept. I rarely created chord charts unless someone else needed and asked for one. However, sharing .mid files and having chord charts is very helpful to me. I have no idea about an E7, for instance, but nowadays I can see a picture of a piano chord instantly, and then I can write it in Reaper.

So essentially I am still rather primitive in my skill set in order to use chord charts, but once I have the piano chord I can play the virtual guitars and synths.

I can also now play chords and read the chords I’m playing, which is interesting if not handy. So basically I might create a chord progression and never know what it is at all.

I also don’t know actual scales, but I can hear them sometimes. I also like to break the rules, but that is harder to do and not sound bad than it may seem to be. I am always listening for something I like.